This is the aftermath of having read 'A Thousand Splendid Suns' by Khaled Hosseini. You can read the review here, and I suggest you do, before reading the following post. For it is very much an extension to what has been said there. Here we go :)

A person who doesn't feel the way others do, Babi here, the two brothers in ‘And the Mountains Echoed’, Idris and Timur. They feel everything, they just don't express. They’re like the men you find in fairy tales, the ones who'd love their princesses to pieces if they ever came to doing it.

Incidentally, all Afghans of his time wanted to do, if they ever went to America was to go there and start a small Afghan restaurant. Abdullah opened on in the previous story, and Babi wanted to have one here. It isn’t a general case, it is just an observation.

A noteworthy excerpt:

"I missed you."

There was a pause. Then Tariq turned to her with a half grinning, half-grimacing look of distaste. "What's the matter with you?"

How many times had she, Hasina, and Giti said those same three words to each other, Laila wondered, said it without hesitation, after only two or three days of not seeing each other? I missed you, Hasina. Oh, I missed you too. In Tariq's grimace, Laila learned that boys differed from girls in this regard. They don't make a show of friendship. They felt no urge, no need, for this sort of talk. Laila imagined it had been this way for her brothers too. Boys, Laila came to see, treated friendship the way they treat the sun: its existence undisputed; its radiance best enjoyed, not beheld directly.

"I was trying to annoy you," she said.

He gave her a sidelong glance. "It worked."

But she thought his grimace softened. And she thought that maybe the sunburn on his cheeks deepened momentarily.

What beauty of expression, and how true is that?

The rhythm, the alarming rise, the devastating fall, the rise again, this is the essence of the story. A man writing from the perspective of woman’s or rather many women’s lives, it is hard. The author does a commendable job at that but, I find a lot of it unreal. Many of the emotions were rather plastic until Aziza was born, until Aziza moved Mariam. And then, oh boy, Aziza did wonders in the story.

The blindness of a fanatic, the desperation to flee, the butterflies, the ‘nothing can go wrong now’ and yet, does; there is no dearth of sadness in what he writes. Funnily enough, Khaled ensures that you’ll remember nothing of the past joy in their pain, the previous pains and hardships in moments of joy, all that the characters remember, all that the readers can remember is a faint scar which shows promise of healing. When the story was drawing to its close, I wasn’t sure, was almost attuned to this rhythm of rise and fall, and had my apprehensions of what trouble awaited Tariq and Laila in Kabul. So many good people had fallen that I did not believe that Tariq wouldn’t have to die until I reached the end of the story.

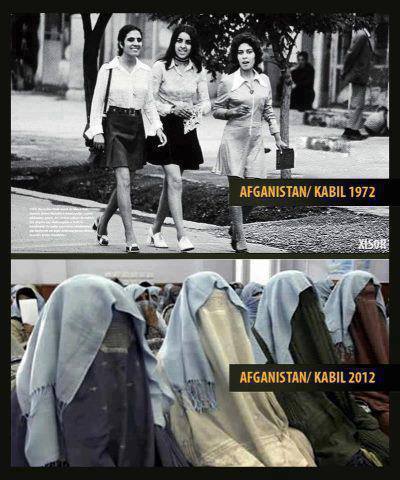

How guileless was Mariam when Rasheed told her that she needed to wear a ‘burqa’. He said “I have customers, Mariam, men, bring their wives to my shop. The women come uncovered, they talk to me directly, look me in the eye without shame. They wear make-up skirts that show their knees. Sometimes they even put their feet in front of me, the women do, for measurements, and the husbands stand there and watch. They allow it. They think nothing of a stranger touching their wives’ bare feet! The think they are being modern men, intellectuals, on account of their education, I suppose. They don’t see that they are spoiling their own nang and namoos, their honour and pride.” Murray didn’t mind it. “In truth, she was even flattered. Rasheed saw sanctity in what they had together. Her honour, her namoos, was something worth guarding to him. She felt prized by his protectiveness. Treasured and significant.” Little did she know that it was all just a farce, a facade built to honey-coat his misogynist conservative attitude. She even found an alternative, sympathetic reason to defend what Rasheed was when she found out a pornographic magazine in his drawer. She had wondered about the character of her husband; “… What about all his talk of honour and propriety, his disapproval of the female customers, who, after all, were only showing him their feet to get fitted for shoes? A woman’s face, he had said, is her husband’s business only. Surely the women on these pages had husbands, some of them must. At the least, they had brothers. If so, why did Rasheed insist that she cover when he thought nothing of looking at the private areas of other men’s wives and sisters?” She concurred that he had been a lonely man, but a man after all and had his desires. She compared him to Jalil and judged him well. Poor girl!

The hypocrisy of men as they differentiate between the law of the state and the law of Islam, it’s appalling. The minuscule nature and stature of women, of their life being trifle, nothing; it is painful and yet you get used to it. It is easy once you know there’s nothing to it, except the highest highs and the lowest lows. As a reader I had at some point wished that Laila and Mariam had succeeded in escaping Afghanistan. But that isn’t quite possible especially in this story because it is a story about Afghanistan; because had they escaped, the story would have been of Pakistan, not Afghanistan. No one can say if they would have survived, but had that happened Khaled wouldn’t have written much of a story either.

My heart was agitated when they blasted the two Buddha statues of Bamiyan (in the book). Civilisations, old and new, wait three, old and new, women were raped indiscriminately - free will suppressed. There is no asking ‘how could they?’ Of course they could, they did. Maybe in some part of the world today or in the distant future there would be people who would refuse to believe that humans are capable of such atrocity and apathy, that man who prides himself to have the most advanced brain and rational thinking can be imprisoned by short-sighted interpretations of scriptures, that fanatic mind-set could overwhelm common sense.

Yet, make no mistake, we have them all around us - they are not limited to a region or religion they’re everywhere. Beware - don’t argue with them - at best, fear them - of rules must be feared as they know not what they are doing. There was only one, Father's son, who died for the sins of the people, but there have been countless mothers and daughters who have laid down their lives and are barely noticed.