By a matter of sheer luck or by divine providence, we, humans have landed in a place from where we can either look out at the cosmos and be humbled by its perceived endlessness, or we can look in, deeper into the structure of which we are made of and be in awe of how the same elements can produce so much diversity from grains of sand to massive stars, and of course, us. Some people choose to look through the telescope, a few through the microscope while another few sit back in their armchairs and observe the world as it unfolds. First came the armchair thinkers, and they brought with them many insightful ideas, some good and some bad. While a few were too uncomfortable with the idea of an ever pervading omnipotent force, God, others, the ones whose ideas then appealed more to masses, readily accepted this concept. But when all three coalesce into a personality who strives to unify them into one cogent theory, we find one of a kind person -Stephen Hawking. It has been an endeavor of science to find that single theory which could explain everything, where every partial theory that we’ve read so far (in school) is explained as a case of the unified theory within some special circumstances.

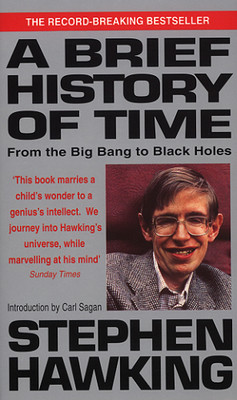

Stephen Hawking has tried to explain the nature of our universe, from the smallest particles which cannot be seen to the biggest entities, the black holes, which (ironically) also cannot be seen, in a simpleton’s language. Barring one mathematical equation, the famous mass energy equivalence relation by Einstein, Hawking has done away with all mathematics and made accessible to a layman the treasures of science and the knowledge of the universe that we have acquired so far (more correctly till the time the book was written) while conjecturing what might be the ingredients of that unified theory.

He has made an honorable attempt at bridging the divide between what the common man knows and what feats science has come to achieve. He explains the reason for this divide as: ‘Up to now, most scientists have been too occupied with the development of new theories that describe what the universe is, to ask the question why. On the other hand, the people whose business it is to ask why, the philosophers, have not been able to keep up with the advances of scientific theories.’ He ascribes this lagging to the mathematics and science becoming ‘too technical and mathematical for the philosophers, or anyone else except a few specialists. Philosophers reduced the scope of their inquiries so much that Wittgenstein, the most famous philosopher of this century, said “The sole remaining task for philosophy is the analysis of language.” What a comedown from the great tradition of philosophy from Aristotle to Kant!’ He has tried to fill in what the general audience has been lacking.

In this brief history of time and science as we know it today, he takes us on a journey from the time when Aristotle and the world of that era believed that Earth was the center of the universe and supported on the back of a giant tortoise to our contemporary age when we know better. It is a brief and enjoyable story of science, the painstaking efforts on the part of scientists and philosophers to explain the world as we see it or as they saw it, the mistakes they committed, and the profound truths that they unraveled.

First, he starts to look out into space. He explain the nature of the stars, their life and their sizes. The various efforts that have helped us understand them better, and in a way, understand our own power house, the sun. We now know, with certain confidence what will become of our sun, and when. From the old tradition of watching the night skies and forming stories and superstitions about them to concepts of heaven and hell to Newton’s law of gravity and to Einstein’s General theory of relativity, we discover how it works and how we’ve come this far. He breaks our notions of absolutes, of how, first, as Newton discovered, space is relative and then nearly 250 years later, Einstein shook the world by showing that time isn’t absolute either and how everything in the world is altering this space time-fabric. One thing leads to another, and then comes a peculiar case of singularity which cannot be explained or surpassed by classical theories - what happens inside the black holes, and what happened during the Big Bang. Incidentally, singularities are usually best avoided by mathematicians (and quantum theory propounds that these two cases might not lead to singularities after all).

Then, he diverts the gaze from the stars to smaller things, searching for answers on the microscopic level - on how things are made, and what they are made of. A new science, Quantum Theory evolves and seems to answer every phenomenon on the microscopic level. Yet, it does not offer answers on the cosmic scale, until attempts are made to unify the two major theories – The Quantum theory of electrodynamics which seems to govern everything small, and the general theory of relativity which dominates large things– into a single unified ‘Quantum theory of gravity’. However, we still hold that ‘Gravity is not the reason why people fall in love’. If you follow close, as exasperating as it might get sometimes - like the unimaginable idea of imaginary time which could hold answers of how it all began and how it will all end, of the existence of God and why the things are the way they are, the Weak Anthropic principle - you will be asking questions all along, and will be rewarded in kind. I for one, quite lost it after Quarks, and had to go through it again before I encountered a picturesque detail of the particle interpretation of gravitons and the weirdness of spin. Can you imagine a particle which if given one rotation would not look like it was before, but if you rotated it twice, would end up looking like it was initially? No? Neither can I, but they are mathematically proven to exist, and much experimental evidence also exists.

Stephen Hawking, as he himself says, has tried to find the nature of God, or later as he corrects, the mind of God in this grand design. He does not disappoint the meta-physicist who is appeased by the idea of divine intervention. In numerous places, he argues with himself over the universe being a work of God, and how did he go about doing it? ‘What did God do before he created the universe? Augustine didn’t reply: He was preparing Hell for people who asked such questions. Instead, he said that time was a property of the universe that God created, and that time did not exist before the beginning of the universe.’ But, as I mentioned earlier, if we can get comfortable with the idea of imaginary time, it could hold the answers of why were are here asking these questions and with some certainty (but not absolutely) what would have happened if this were not the case, which leaves God pretty much on the bench for a long, long time.

The book is beautiful in a way that it is presented. It is a fun read, but be wary that the jump into the quantum domain can turn the best of believers into agnostic worriers, so give some allowance to doubt. It might all be an illusion after all, with us living in the imaginary while thinking that the real is imaginary, something like living inside a mirror and thinking that the real person is our mirror image. It might all lead to zero, everything coming out of nothing, and yet amounting to nothing (which would be very frustrating to find out after going through all this). As is often quoted in the religious books – Seek, and Ye shall find!

P.S.: There is a little thought trail that I managed to record while it was escaping me after reading some part of this book. You can read it here.